hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Fearing restrictions on foreign student recruitment, Korean schools take immigration raids into their own hands

A former student at Hanshin University’s Korean language academy, Kulkar Amirkulova had dreamt of studying in Korea since she was in middle school. She’d even given herself a Korean name: Woo Ji-soo. She took her name from the protagonist of a web series about high schoolers going through growing pains. After trying to convince her parents for two years, she finally got on a flight to Korea in September 2023. Her plans were to learn Korean, enroll at a Korean university, and become a flight attendant or designer.

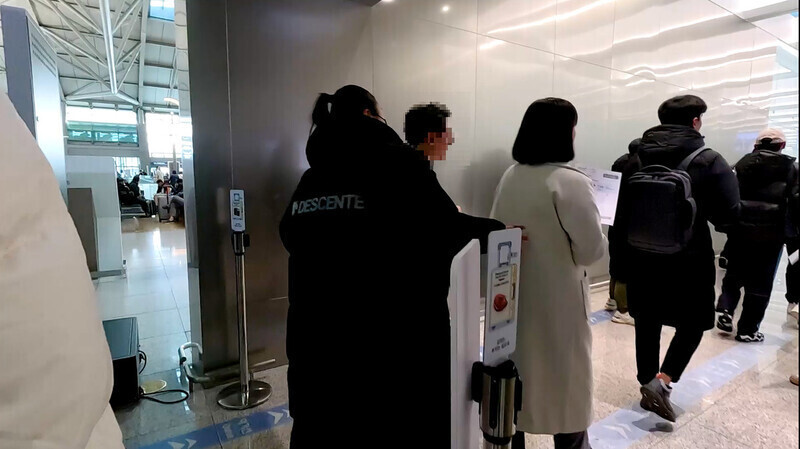

But her dreams were shattered just two months later on Nov. 27, 2023. She boarded a bus with other language school students from her homeland of Uzbekistan after being told by her school that they needed to visit the immigration office to pick up their residence cards. She and the other students were shuttled to Incheon International Airport and forced on a plane back to Uzbekistan. Amirkulova says she doesn’t remember much of what happened that day.

“When I heard we were being taken to the airport, my ears started ringing. My head hurt,” she said. “Why did they do that to us?”

Hanshin University has claimed its actions were based on “educational interests.”

“We had no choice but to guide them out of the country after they failed to maintain the minimum balance in their bank accounts,” said a university employee.

“Our actions were based on educational interests, to prevent the students from becoming illegal aliens,” the employee added.

Yet the real reason behind the forced deportations was clear: money.

As South Korea’s fertility rate continues to plummet, Korean universities are facing financial difficulties. The country’s population of students is diminishing. They have turned to recruiting more international students to fill their coffers. The problem, however, is that many students end up dropping out after finding work. The South Korean government restricts universities from issuing student visas if the number of enrolled students who become unregistered sojourners exceeds a certain standard. Hanshin University was basically covering its own bases by forcing the Uzbek students out of the country before they so much as had a chance to become undocumented migrants.

It is the Justice Ministry’s job to handle matters related to monitoring foreign residents and cracking down on violations. Yet Hanshin University acted in its stead. And this isn’t the first time a university has acted as a de facto immigration authority. It’s not uncommon for university employees to act as immigration enforcement agents and chase down foreign students. In May 2023, News N Joy and MBC reported on human rights violations of Vietnamese students at Jeonju Kijeon College.

At the time, the college put up photographs in the offices of its Korean language and culture education center showing students who had been deported after being caught leaving the school, each emblazoned with the word “OUT” in red letters. It also put up photographs of security officers seizing these students by both arms. It was alleged that students were kept in confinement during the deportation process.

The college explained that these actions were taken for “educational purposes.” It told the press that its operation of a de facto arrest squad for straying students was an “unavoidable step taken to avoid the university facing visa issuance restrictions.”

Explaining its reasons for enlisting the services of security workers, the college said, “We’re the ones capturing them, but because there are times when [students] suddenly flee and unexpected incidents can arise, [security workers] accompany them when they’re being deported.”

In this way, Jeonju Kijeon College was able to avoid being subjected to visa issuance restrictions that restrict recruitment of international students — at the cost of igniting controversy over human rights violations.

Each year, the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Justice conduct examinations of how international students are recruited and managed.

But their assessments focus on areas such as the rates of undocumented sojourns, the numbers of language students per class, health insurance enrollment, the percentage of certified Korean language instructors, and the rate of language study program completion. Whether human rights are being respected is not their concern.

As a result, schools engage in the kind of blatant violations of international student human rights that would be unthinkable if applied to South Korean students.

The university officials that the Hankyoreh met with in its investigation said such practices are commonplace throughout the country.

“Hanshin University’s actions were extreme, but it may have concluded from its standpoint that it would be better to deport the students like that than to face visa issuance restrictions,” said an official at a university-affiliated language center outside the greater Seoul area.

Another official with the international relations team at a university in the greater Seoul area said, “The Ministry of Justice creates an unrealistic system, and all the responsibility for the side effects from that gets foisted on universities.”

“The logic is that the schools are the ones selecting the students, so the schools end up focusing on monitoring their students,” they explained.

International students are calling for sterner punishments for human rights violations by universities.

Abdoul, a 25-year-old providing interpreting support for Uzbek students at Hanshin University, said the situation “is the result of them viewing international students simply as a way of making money.”

“I’d like to see the South Korean government take this opportunity to conduct a full-scale investigation of the international student human rights situation here,” he added.

By Lee Jun-hee, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1Behind-the-times gender change regulations leave trans Koreans in the lurch

- 2South Korean ambassador attends Putin’s inauguration as US and others boycott

- 3Family that exposed military cover-up of loved one’s death reflect on Marine’s death

- 4Yoon’s broken-compass diplomacy is steering Korea into serving US, Japanese interests

- 5Yoon’s revival of civil affairs senior secretary criticized as shield against judicial scrutiny

- 6Marines who survived flood that killed colleague urge president to OK special counsel probe

- 7AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 8Japan says its directives were aimed at increasing Line’s security, not pushing Naver buyout

- 9[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 101 in 10 marriages in Korea last year was with a foreign national